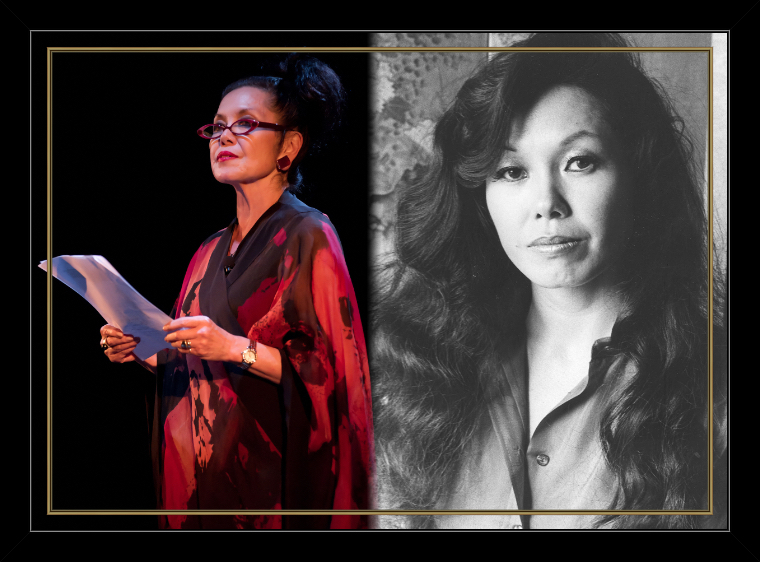

Salute to a Soul Sister

(Graphic: Brian Covert / Photos: Alain McLaughlin, Nancy Wong)

Janice Mirikitani and a friend are walking down the sidewalk, as the friend’s recollection goes, in the Tenderloin district of San Francisco, California, USA — one of the city’s poorer and more merciless areas. Coming down the sidewalk toward them is a man of the streets who is making loud barking and growling noises like a dog; he is obviously in need of some help.

The friend instinctively grabs Mirikitani’s arm to pull her away and out of the path of a perceived danger looming ahead. Just as instinctively, Mikiritani pulls the friend back close to her and keeps walking straight ahead, her stride intact. Soon, the man and Janice are standing face to face on the sidewalk and the friend’s heart is racing, fearing what might come next.

But without any fear of her own, Mirikitani looks up at the man’s face, places her hand over his heart and tells him, “I love you”. Then she adds: “How can I heal you? Are you hungry?” The man moves on down the sidewalk without incident, the friend’s nerves are shattered, and some healing has occurred right there in the streets, whether anyone notices it or not.

This episode, related by the friend during a three-hour public memorial service recently for the late Janice Mirikitani, illustrates perhaps better than any other what made Mirikitani tick, why she is so beloved by the people of the city and beyond, and why her recent passing at age 80 is so deeply mourned, especially by those whose lives she personally touched.

Feeder of the hungry, shelterer of the homeless, staunch advocate for women and children, a poet-warrior, a dancer, an educator: Janice Mirikitani was all these things and more. Collective and personal pain and struggle marked her early years, yet by the end of her long life, she had transformed those traumas and scars into healing, putting a high spiritual love into practice on a daily basis.

To most of the general public, she was well known as the co-leader — along with her husband, Pastor Cecil Williams — of San Francisco’s Glide Memorial Church, a Methodist Christian church that has long served as a welcoming haven for the downtrodden and broken ones in society, the wretched of the earth who nobody else would take in. Mirikitani and Williams would go on to become a moral force to be reckoned with over the years, their loving partnership a Bay Area institution in its own right.

To the people of the streets, though, Mirikitani was affectionately and respectfully referred to as The First Lady of the Tenderloin, the San Francisco district where Glide church is located: a caring, loving soul sister to all and a rejecter of none.

Janice Hatsuko Mirikitani was born in early 1941 as a third-generation (sansei) Japanese American in the northern San Joaquin Valley city of Stockton, California, where her parents ran a poultry farm. Ten months after Mirikitani’s birth, in December 1941, the military forces of Japan attacked the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, an island chain that was then being colonized by the U.S. The Pacific War was on.

Suddenly, Mirikitani and all Japanese-American citizens who looked like her were suspected of being collaborators of Japan, the enemy nation. So began one of the most shameful periods in American history, in which more than 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry in the United States — most of them being U.S. citizens and about half of them being children — were summarily rounded up and sent off to concentration camps scattered around the United States. Mirikitani was just one year old when her family was uprooted from California and sent to the Rohwer War Relocation Center in rural Arkansas in the southern United States. More than 8,400 Japanese Americans would join her there in that prison camp, surrounded by barbed wire and armed military guards and victimized by raw hate and poverty.

For many Japanese Americans who experienced it, “the camps” would prove to be a bitter, lifelong traumatizing experience. Their own country, the USA, had let them know in no uncertain terms that they were different from other Americans and were not to expect to be treated better than second-class citizens at most. Many Japanese-American citizens died in those concentration camps and would never walk out as free people again.

With the end of the Second World War and the family’s release back into society, Mirikitani was pushed from one traumatic experience into another: Starting from around age five, she was forced to deal with more years of poverty and emotional isolation, compounded by sexual abuse by her stepfather that lasted for a decade until she was around 16. Her repressed emotions over these hardships would form the deep roots of her poetry in the years to come.

It was in the poetic word, both reading and writing it, where Mirikitani said she found true freedom from the personal and societal oppression around her. She thought of poetry not as a bunch of nice-sounding words, but as a lifesaving device and even a potent weapon against American racism and prejudice.

Listen, for example, to her recite her poem “Attack the Water” back in the 1970s about America’s genocidal war on the southeast Asian nation of Vietnam and how it related to Japanese-American life in America’s domestic concentration camps in World War II. Read her poems, like “For a Daughter Who Leaves”, in which she so eloquently captures the spirit of the Asian-American experience.

In 2000, Mirikitani became the second poet laureate for the city of San Francisco and a collection of her writings, Love Works, was released. “Poetry has been, for me, the language of my definition and my liberation,” she said in her inaugural address. “For me, poetry should be accessible, connecting our human experiences, steeped in the struggles that define us. Poetry gives form to the power of imagination and speaks as the conscience of real life.”

As head of some of the Glide Memorial Church’s community outreach programs, she would use poetry as an integral part of the recovery process for women who were suffering from drug addiction and past sexual abuse. It was all tied together.

Mirikitani was highly educated and multi-talented, and could have chosen any career path she wanted. Instead, she found her life’s calling in standing on the side of the beaten down and oppressed ones in American society — most of whom, she recognized, were people of color — attending to their immediate needs with food and shelter, and working to spiritually uplift and physically and mentally empower them at the same time she was uplifting and empowering herself.

In her later years, she was also a respected elder who was asked to come back to her old university in 2014 and teach again as a diversity scholar. She brought her years of social activism in the so-called outside world right into the classroom; there would be no separating the streets from the schools for her.

Mirikitani had published four collections of poetry in her lifetime and edited a few others. Two of her works are slated to be reissued together by the University of Washington Press later this year — a must-read for anyone wanting to remember and understand one of the truly great author-activists of our time. Her personal odyssey is also recounted in this excellent interview by phati’tude Literary Magazine, published by 2Leaf Press, a Black/Brown female-led press based in New York.

And so, in words and with a raised fist, we salute Janice Mirikitani, a sister who cared heart and soul for the well-being and wellness of others and who worked tirelessly to make a positive difference in the world. But of course, as with all things American, there is always more work to be done in dealing with racism, economic disparity, political disenfranchisement, environmental degradation and spiritual starvation, to name a few. In many ways, the real righteous fight begins now. Although this sister has recently gone from our midst, her legend, her work and her inimitable style and swing will surely live on in people’s hearts and help guide us through the perilous paths ahead.