Accolades for the Archbishop

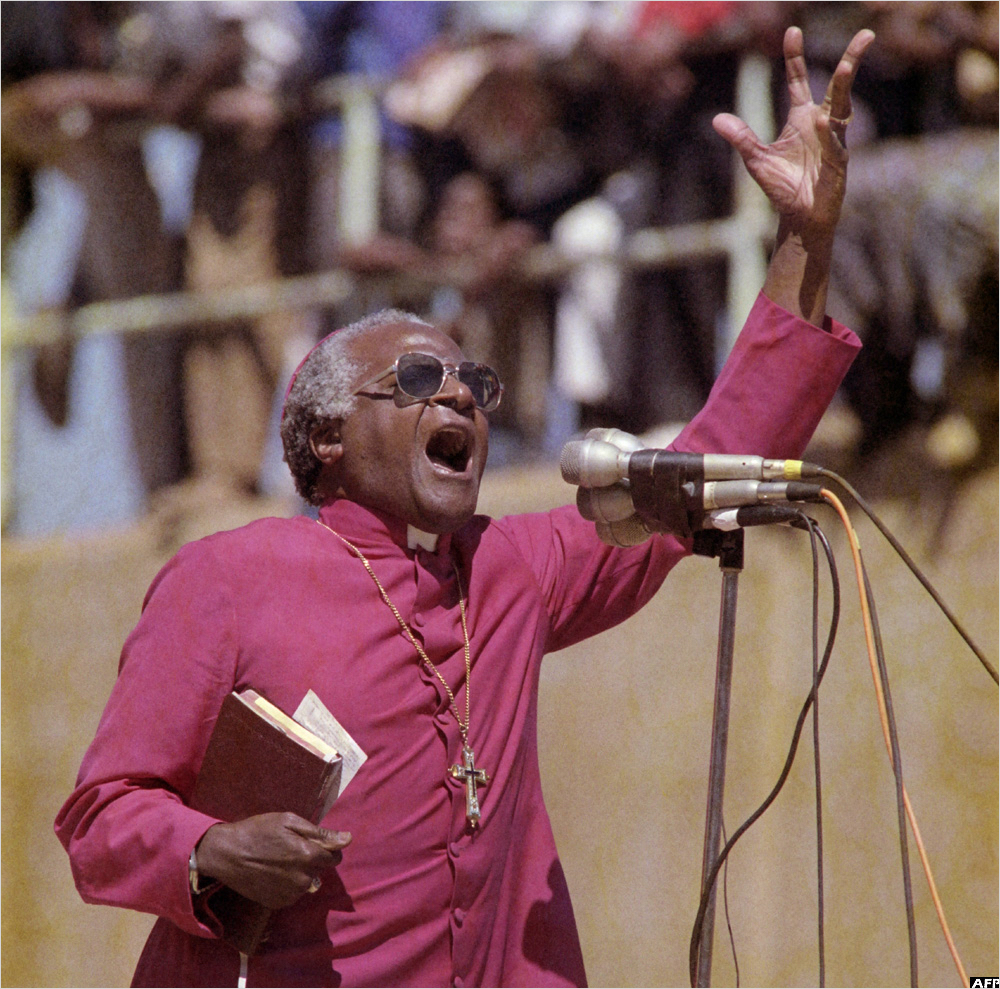

Archbishop Desmond Tutu speaking at a Soweto stadium, 1990 (Photo: AFP)

It is early morning somewhere in rural South Africa, the sun not yet rising over the horizon. In the dim morning light, through the slowly lifting fog — or is it smoke from the nearby shacks? — I am walking up some makeshift steps on the side of a steep ravine. I look over at the person walking up next to me and study the lines on his face: It is Desmond Tutu, the revered Anglican Church archbishop of South Africa. He is showing me around here, he explains, because he wants me to see how people in South Africa really live, the poverty they still have to face in the land of apartheid.

We are at a squatter camp on the side of a steep hill or mountain, peppered with shacks of tin, wood and cardboard where Black South Africans are forced to live in desperation because the whites in the country have hoarded all the wealth for themselves. The deep poverty around us here is grinding, and heartbreaking. As we walk up the steep grade together, just the two of us, I see and feel a profound sense of grief on Tutu’s face and I know that he truly cares for these people, among the most downtrodden in all of South Africa.

Suddenly, the time is up, and the morning light of reality jars my mind awake. It was all just a dream — a dream so vivid and clear and humbling, in fact, that I can still remember it many years later. It was this dream that I instantly recalled when the news came through about the passing of Archibishop Desmond Tutu in South Africa on 26 December 2021 at age 90.

It was Tutu’s genuine concern, care and love for his people in South Africa, and for the plight of people everywhere by extension, that made him such a revered icon around the world. But not only that: He was a moral man who never hesitated to stand up on the side of the dispossessed and oppressed ones in South Africa and beyond, fighting the good fight right alongside them with the power of nonviolence and soul-force. In a world full of religious fakers and frauds, Archbishop Tutu — or Arch, as he was affectionately called — was the real deal.

When the top-ranking liberation leaders in South Africa like Nelson Mandela were imprisoned, assassinated, in exile or “banned” as persona non grata by apartheid government decree, it was Tutu who became the moral leader of Black South Africa, facing possible arrest and death himself at every turn, especially during the turbulent 1970s and 1980s.

Tutu could be found in those days delivering his passionate Anglican Church sermons just as often as he could be found giving the last words at the gravesites of ordinary Black South Africans killed by the white police. During an outdoor memorial service in 1977 attended by thousands of South Africans, Tutu delivered the eulogy for the young Black Consciousness leader Steve Biko, who had been tortured and killed by South Africa’s security police while in detention.

When Tutu was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in October 1984, the world rejoiced with him. I certainly did: As a student editor during my university years, I insisted on writing the editorial for a campus newspaper at the time honoring the new Nobel laureate as a “true man of peace”. I understood, as many South Africans in the anti-apartheid movement did back then, that Tutu’s Nobel prize would be a much-needed moral weapon in helping to strike down the immoral and illegal system of racial segregation and division in that country.

To many whites in South Africa, however, Tutu was the devil incarnate. His receiving the Nobel prize back then, as I wrote in the editorial, was dismissed by whites as “part of a Communist conspiracy to promote a Black revolution”. But by all accounts, the only really wicked thing about Desmond Tutu was his sense of humor. He was quick with a laugh and a joke, and was always open in expressing his emotions. And yet the white apartheid government in South Africa saw him as part of a Communist threat, much like certain elements of the United States government did with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in his day.

Nelson Mandela is rightly revered as the father of the nation, following the apartheid regime’s downfall and the first-ever democratic elections in South Africa in 1994. But it would be wise to remember that Archbishop Tutu was far more progressive and even more radical than stalwarts like Mandela in the African National Congress (ANC). Tutu never hesitated to lend his name to the cause of human rights anywhere in the world, wherever injustice raised it ugly head.

I can still remember how Tutu came from South Africa to join a massive anti-war march in the streets of New York City in early 2003 to protest the impending U.S. invasion of Iraq. His speech that day before an audience of thousands only strengthened his high standing in the pantheon of the great moral leaders of our time. We were out there in our millions in the streets of cities around the world in support of peace and against war, and Tutu was with us too.

When the ANC, the governing party in South Africa, started becoming corrupt, Tutu spoke out against that too. In one memorable episode in 2011, Tutu severely criticized his own government for not allowing the Tibetan Buddhist leader the Dalai Lama to enter South Africa (presumably due to pressure from China, an important trading partner of South Africa).

Tutu stood alone among the other great religious leaders of our time when he called in 2012 for former U.S. president George W. Bush and ex-British prime minister Tony Blair to be prosecuted by the International Criminal Court for their role in carrying out the invasion of Iraq a decade earlier. Tutu was right. Of course, he was giving voice to millions of other people in the international community who felt strongly about the issue.

In 2013, to the great shock of many, Tutu came out and publicly disavowed the ANC and its leadership in South Africa. As harsh as his words sounded, he was absolutely correct. He knew from firsthand experience what he was talking about; many South Africans had been feeling exactly the same way for years.

Tutu was no slouch, either, when it came to rapture. The Book of Joy, published by Random House in 2016, features a series of dialogues between Tutu and the Dalai Lama. I highly recommend it to anyone who could use some literary upliftment in their lives. Bridging the gap between Christianity and Buddhism, between the West and East, Tutu and the Dalai Lama make the case for love, peace, nonviolence, forgiveness and compassion better than anyone else has in these chaotic times. A new film about their encounters, Mission: Joy, released in 2021, catches the magic of these two elderly spiritual brothers on video.

For me, personally, Archbishop Desmond Tutu was a spiritual father in the most respectful sense of the word. He was firm but flexible in his convictions, sometimes brutally frank, but always on the right side of morality without being a demagogue or a typical Christian preacher full of double standards.

Another giant tree in the forest has fallen and the loss is widely felt across the globe. Accolades are running high for the life and legacy of Archbishop Desmond Tutu, just as they should be, and I will gladly add mine to them. There may be another big gap now in the forest where this giant redwood of a man once stood — or in my case, on a mountainside trail as I once dreamed it — but that new clearing only leaves space for us all to follow as best we can in his footsteps.

Hamba kahle, Tata Tutu (Go well, Father Tutu), as folks are saying in the native Xhosa language of South Africa following the death of their beloved Arch. And that goes double for me.