Hamba Kahle to a South African Son

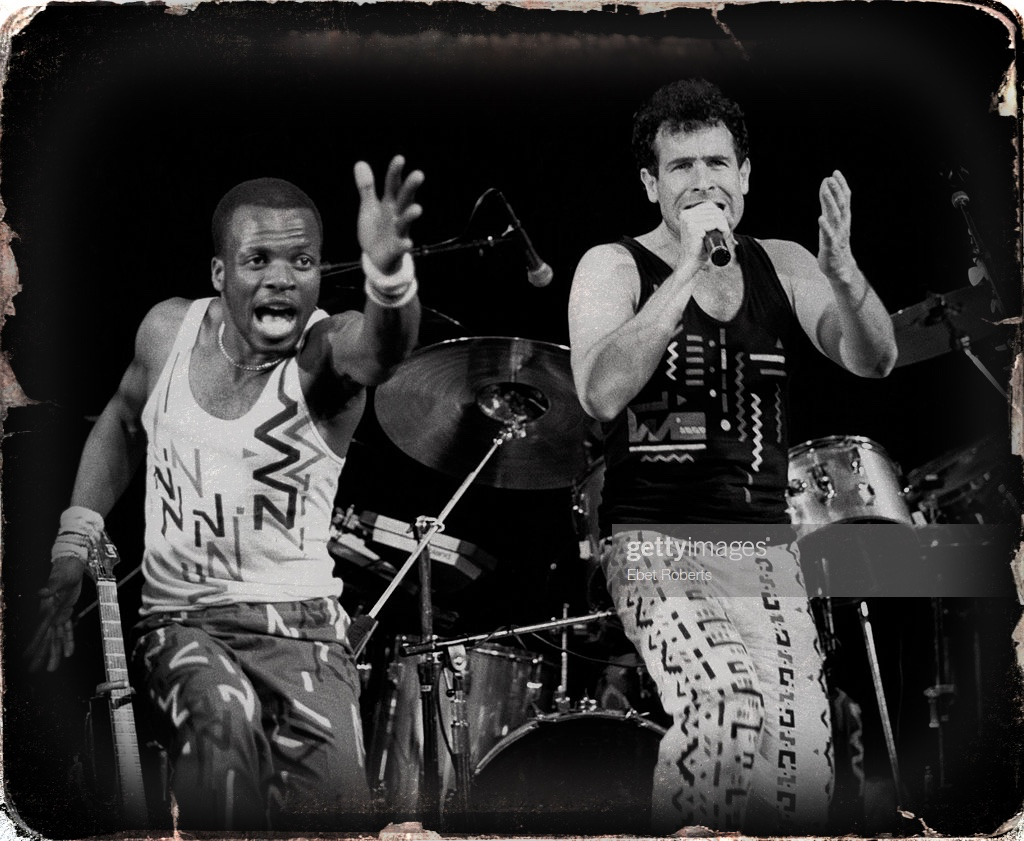

(Graphic: Brian Covert / Photo: Getty Images)

Hamba kahle in the Xhosa and Zulu languages of South Africa is a commonly expressed heartfelt wish for a deceased person to “go well” on their spiritual journey in the Great Beyond. Another commonly heard English phrase at South African funerals is that someone “ran a good race” during his/her lifetime on Earth, having lived a life worthy of praise.

Such terms of endearment are among the many now being expressed throughout South Africa for renowned musician Johnny Clegg, who passed away at his home in Johannesburg a few days ago at the all-too-young age of 66. He had succumbed to pancreatic cancer.

Though a white South African, Clegg immersed himself in the traditional Zulu culture and language of his country at a young age, and in the 1970s and 1980s, he formed bands that brought a unique South African musical crossover brew to domestic audiences, and then to the outside world, to popular acclaim.

Especially during some of the worst years of apartheid, South Africa’s brutally enforced system of racial segregation, artists like Clegg and his African bandmates could be jailed — and actually were at times — for performing together publicly in multiracial concerts. It was a very dangerous time to reach across the walls of racial separation that were imposed by the state in South Africa. And yet Clegg did just that.

The two bands he formed with his Zulu compatriots — the bands Juluka and Savuka — effectively crossed musical borders in the country, skirting apartheid laws whenever they could, and telling stories of what it meant to be both black and white in a country with a politically psychotic form of government that South Africans were living under in those years. And the bands did it all while singing in both Zulu and English, and performing traditional Zulu dance, always bringing the house down in their live shows.

The album Third World Child in 1987 was the breakthrough record that put Clegg and the Savuka band on the international map, and that is where I first encountered their music here in Japan. It was Afro-pop with a uniquely South African flavor and, its own way, was much more political than other mainstream recording bands in that country. The only thing that probably kept Clegg out of a South African jail following Third World Child is that the record was released by a major overseas record label, EMI Records of Britain, a form of protection by popular exposure.

Along with many other folks around the world, I was hooked on the music of South Africa at the time, and became an instant fan of Johnny Clegg and his music. He wasn’t the strongest vocalist on the South African scene — his voice was kind of thin and shaky — but his heart and talent were in the right place, and he had genuine credibility and legitimacy among South Africa’s majority black population. That was good enough for me.

Clegg certainly had much more credibility among South Africans than, say, Paul Simon of the United States and his hugely popular South African-influenced album, Graceland, which was released around the same time. Clegg was the real deal, using his artistry to reflect the turbulence of the times and to sing of better days to come for South Africans beyond apartheid.

More than 30 years later, Third World Child sounds as great as it did back in 1987. I challenge anyone reading these words to listen right now to the whole album in its entirety, from start to finish, and not be moved by the music and message it contains.

One of the songs from the album, “Asimbonanga (Mandela)”, went on to become an anthem of sorts, both in South Africa and globally, written as it was while Nelson Mandela was still imprisoned on Robben Island off the coast of South Africa and unseen by the public for decades. Mandela himself was said to be a big fan of this song.

That was evident years later, after South Africa achieved its freedom and Mandela had just stepped down as president of the country: Clegg opened a concert in Frankfurt, Germany in 1999 with that song, and Mandela, who happened to be in Europe around the same time, made an unannounced appearance at Clegg’s concert during the performing of that tune. Clegg later called that surprise stage appearance, with Mandela doing his famous “Madiba dance”, the high point of the musician’s life. It was a classic moment caught on film.

Clegg went on to a distinguished career as a musician, carrying his post-apartheid credentials to warm, accepting audiences everywhere as a son of South Africa. In 2015, Clegg was diagnosed with cancer and he decided to do one more tour in 2017 — The Final Journey, he called it — to say goodbye and thanks to fans. He lasted another two years after the tour, then departed for good just a few days ago, amidst accolades from black and white South Africans alike.

Clegg was a musical pioneer at a time of immense struggle, and if our world has become a better place in the decades since then, it is due in no small part to people like him everywhere across the social spectrum who give fully of themselves and have the courage to stand on the side of love over hate. Sixty-six is far too young an age for anyone to die these days, but it is reassuring to know that Clegg’s music and legacy will live on for many more years to come.

So, as they say in South Africa: Hamba kahle, brother Johnny Clegg. Go well with the spirits of the other legendary South Africans who have passed on before you, and may the journey onward from here be a good one. You ran a good race all the way to the end. And we are all the richer for it.